|

Glenoid fossa of right side. (Glenoidal labrum labeled as "glenoid lig.")

|

The shoulder joint is a 'ball and socket' joint. However, the 'socket' (the glenoid fossa of the scapula) is small, covering at most only a third of the 'ball' (the head of the humerus). It is deepened by a circumferential rim of fibrocartilage, the glenoidal labrum. Previously there was debate as to whether the labrum was fibrocartilaginous as opposed to hyaline cartilage found in the remainder of the glenoid fossa. Previously, it was considered a redundant, evolutionary remnant, but is now considered integral to shoulder stability. Most agree that the proximal tendon of the long head of the biceps brachii muscle becomes fibrocartilaginous prior to attaching to the superior aspect of the glenoid. The long head of the triceps brachii inserts inferiorly, similarly. Together, all of those cartilaginous extensions are termed the 'glenoid labrum'.

A SLAP tear or lesion occurs when there is damage to the superior (uppermost) area of the labrum. These lesions have come into public awareness because of their frequency in athletes involved in overhead and throwing activities in turn relating to relatively recent description of labral injuries in throwing athletes, and initial definitions of the 4 (major) SLAP sub-types, all happening since the 1990s. The identification and treatment of these injuries continues to evolve.

Although ten varieties of SLAP lesion have been described on MRI or MR arthrography seven clinical types are generally described.

Several symptoms are common but not specific:

Few with SLAP lesion injuries return to full capability without surgical intervention. In some, physical therapy can strengthen the supporting muscles in the shoulder joint to the point of reestablishing stability. For most others, the choice is to do nothing or some form of surgical repair.

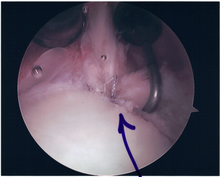

While surgery can be performed as a traditional open procedure, an arthroscopic technique is currently favored being less intrusive with low chance of iatrogenic infection.

Associated findings within the shoulder joint are varied, may not be predictable and include:

It should be noted that while good outcomes with SLAP repair over the age of 40 are reported, both age greater than 40 and Workmen's Compensation status have been noted as independent predictors of surgical complications. This is particularly so if there is an associated rotator cuff injury. In such circumstances, it is suggested that labral debridement and biceps tenotomy is preferred.

SLAP (Superior Labral Tear, Anterior to Posterior)

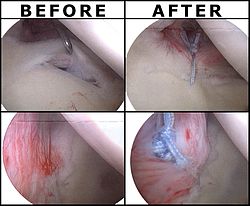

Following inspection and determination of the extent of injury, the basic labrum repair is as follows.

Surgical rehabilitation is vital, progressive and supervised.

The first phase focusses on early motion and usually occupies post-surgical weeks one through three. Passive range of motion is restored in the shoulder, elbow, forearm, andwrist joints. However, while manual resistance exercises for scapular protraction, elbow extension, and pronation and supination are encouraged, elbow flexion resistance isavoided because of the biceps contraction that it generates and the need to protect the labral repair for at least six weeks. A sling may be worn, as needed, for comfort.

Phase 2, occupying weeks 4 through 6, involves progression of strength and range of motion, attempting to achieve progressive abduction and external rotation in the shoulder joint.

Phase 3, usually weeks 6 through 10, permits elbow flexion resistive exercises, now allowing the biceps to come into play on the assumption that the labrum will have healed sufficiently to avoid injury. Thereafter, isokinetic exercises may be commenced from weeks 10 through 12 to 16, for advanced strengthening leading to return to full activity based on post surgical evaluation, strength, and functional range of motion. The periods of isokinetics through final clearance are sometimes referred to as phases four and five.

|

Page Content |