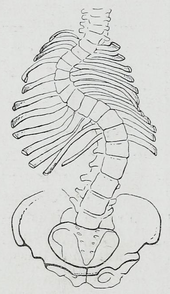

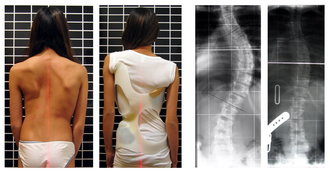

Scoliosis is a common medical condition in which a person's spinal axis has a three-dimensional deviation. Although it is a complex three-dimensional condition, on an X-ray, viewed from the rear, the spine of an individual with scoliosis can resemble an "S" or a "C", rather than a straight line.

Scoliosis is typically classified as either congenital (caused by vertebral anomalies present at birth), idiopathic (cause unknown, sub-classified as infantile, juvenile, adolescent, or adult, according to when onset occurred), or secondary to a primary condition.

| Scoliosis | |

|---|---|

|

|

Secondary scoliosis can be the result of a neuromuscular condition (e.g., spina bifida, cerebral palsy, spinal muscular atrophy, or physical trauma) or syndromes such as Chiari malformation.

Recent longitudinal studies reveal that the most common form of the condition, late-onset idiopathic scoliosis, causes little physical impairment other than back pain and cosmetic concerns, even when untreated, with mortality rates similar to the general population. Older beliefs that untreated idiopathic scoliosis necessarily progresses into severe (cardiopulmonary) disability by old age have been refuted by later studies. The rarer forms of scoliosis pose risks of complications such as heart and lung problems. Scoliosis is a lifelong condition; management of the condition includes treatments such as bracing, physical therapy and surgery.

People who have reached skeletal maturity are less likely to have a worsening case. Some severe cases of scoliosis can lead to diminishing lung capacity, pressure exerted on the heart, and restricted physical activities.

The signs of scoliosis can include:

Scoliosis is sometimes associated with other conditions, such as Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (hyperflexibility, "floppy baby" syndrome, and other variants of the condition), Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease, Prader–Willi syndrome, osteogenesis imperfecta, kyphosis, cerebral palsy, spinal muscular atrophy, muscular dystrophy, familial dysautonomia, CHARGE syndrome, Friedreich's ataxia, fragile X syndrome, proteus syndrome, spina bifida, Marfan's syndrome, nail–patella syndrome, neurofibromatosis, connective tissue disorders, congenital diaphragmatic hernia, hemihypertrophy, and craniospinal axis disorders (e.g., syringomyelia, mitral valve prolapse, Arnold–Chiari malformation), and amniotic band syndrome. It is also associated with Loeys-Dietz syndrome.

Scoliosis associated with known syndromes such as Marfans or Prader–Willi is often subclassified as "syndromic scoliosis".

Pain in the lower or upper shoulder blade, neck and buttock pain nearest bottom of the back. Nerve pinching of the leg may cause the legs to cut out.

Among females, painful menstruation (dysmenorrhea) might be prevalent due to a secondary pelvic tilt.

There are many causes of scoliosis, including congenital spine deformities (those present at birth, either inherited or caused by the environment), neuromuscular problems, genetic conditions, and limb length inequality. Other causes for scoliosis include cerebral palsy, spina bifida, muscular dystrophy, spinal muscular atrophy, and tumors.

An estimated 65% of scoliosis cases are idiopathic, about 15% are congenital and about 10% are secondary to a neuromuscular disease.

Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) has no clear causal agent, and is generally believed to be multifactorial, although genetics are believed to play a role. The prevalence of scoliosis is 1% to 2% among adolescents, however the likelihood of progression among adolescents with a Cobb angle of less than 20° is about 10% to 20%.

Congenital scoliosis can be attributed to a malformation of the spine during weeks three to six in utero. It is a result of either a failure of formation, a failure of segmentation, or a combination of stimuli. This incomplete and abnormal segmentation results in an abnormally shaped vertebra, at times fused to a normal vertebra or unilaterally fused vertebrae, leading to the abnormal lateral curvature of the spine.

Secondary scoliosis due to neuropathic and myopathic conditions can result in a loss of muscular support for the spinal column which results in the spinal column being pulled in abnormal directions. Some conditions which may cause secondary scoliosis include muscular dystrophy, spinal muscular atrophy, poliomyelitis, cerebral palsy, spinal cord trauma, and myotonia. Scoliosis often presents itself, or worsens, during the adolescence growth spurt and is more often diagnosed in females than males.

Scoliosis is commonly marked by calcium deposits (ectopic calcification) in the cartilage endplate and sometimes in the disc itself.

Scoliosis is defined as a spinal curvature of more than 10 degrees to the right or left as the examiner faces the patient (in the coronal plane). Deformity may also exist to the front or back (in the sagittal plane).

Patients who initially present with scoliosis are examined to determine whether the deformity has an underlying cause. During a physical examination, the following are assessed to exclude the possibility of underlying condition more serious than simple scoliosis.

The patient's gait is assessed, and there is an exam for signs of other abnormalities (e.g., spina bifida as evidenced by a dimple, hairy patch,lipoma, or hemangioma). A thorough neurological examination is also performed, the skin for café au lait spots, indicative of neurofibromatosis, the feet for cavovarus deformity, abdominal reflexes and muscle tone for spasticity.

During the examination, the patient is asked to bend forward as far as possible. This is known as the Adams forward bend test and is often performed on school students. If a prominence is noted, then scoliosis is a possibility and the patient should be sent for an X-ray to confirm the diagnosis.

As an alternative, a scoliometer may be used to diagnose the condition.

When scoliosis is suspected, weight-bearing full-spine AP/coronal (front-back view) and lateral/sagittal (side view) X-rays are usually taken to assess the scoliosis curves and the kyphosis and lordosis, as these can also be affected in individuals with scoliosis. Full-length standing spine X-rays are the standard method for evaluating the severity and progression of the scoliosis, and whether it is congenital or idiopathic in nature. In growing individuals, serial radiographs are obtained at three- to 12-month intervals to follow curve progression, and, in some instances, MRIinvestigation is warranted to look at the spinal cord.

The standard method for assessing the curvature quantitatively is measurement of the Cobb angle, which is the angle between two lines, drawn perpendicular to the upper endplate of the uppermost vertebra involved and the lower endplate of the lowest vertebra involved. For patients with two curves, Cobb angles are followed for both curves. In some patients, lateral-bending X-rays are obtained to assess the flexibility of the curves or the primary and compensatory curves.

Through a genome-wide association study, geneticists have identified single nucleotide polymorphism markers in the DNA that are significantly associated with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Fifty-three genetic markers have been identified. Scoliosis has been described as a biomechanical deformity, the progression of which depends on asymmetric forces otherwise known as the Heuter-Volkmann law.

The traditional medical management of scoliosis is complex and is determined by the severity of the curvature and skeletal maturity, which together help predict the likelihood of progression. The conventional options for children and adolescents are:

For adults, treatment usually focuses on relieving any pain:

Treatment for idiopathic scoliosis also depends upon the severity of the curvature, the spine’s potential for further growth, and the risk that the curvature will progress. Mild scoliosis (less than 30 degrees deviation) may simply be monitored and treated with exercise. Moderately severe scoliosis (30–45 degrees) in a child who is still growing may require bracing. Severe curvatures that rapidly progress may be treated surgically with spinal rod placement. Bracing may prevent a progressive curvature, but evidence for this is not very strong. In all cases, early intervention offers the best results. A growing body of scientific research testifies to the efficacy of specialized treatment programs of physical therapy, which may include bracing.

Physical Therapists and Occupational Therapists helps those who have experienced an injury or illness regain or maintain the ability to participate in everyday activities. For those with scoliosis, a physical therapist and/or occupational therpaist can provide assistance through assessment, intervention, and ongoing evaluation of the condition. This helps them manage physical symptoms and/or use compensatory techniques so that they can participate in daily activities like self-care, productivity, and leisure.

One intervention involves bracing. During the past several decades, a large variety of bracing devices have been developed for the treatment of scoliosis. Studies demonstrate that preventing force sideways across a joint by bracing prevents further curvature of the spine in idiopathic scoliosis, while other studies have also shown that braces can be used by individuals with scoliosis during physical activities.

Other interventions include postural strategies, such as posture training in sitting, standing, and sleeping positions, and in using positioning supports such as pillows, wedges, rolls, and corsets.

Adaptive and compensatory strategies are also employed to help facilitate individuals to returning daily activities.

Strengthening spinal muscles is a crucial preventive measure. This is because the muscles in the back are essential when it comes to supporting the spinal column and maintaining the spine's proper shape. Exercises that will help improve the strength of the muscles in the back include rows and leg and arm extensions. Elastic resistance exercise may also be able to sustain the progression of spinal curvature. This type of exercise is able to sustain progression by equalizing the strength of the torso muscles found on each side of the body.

Disability caused by scoliosis, as well as physical limitations during recovery from treatment-related surgery, often affects an individual’s ability to perform self-care activities. One of the first treatments of scoliosis is the attempt to prevent further curvature of the spine. Depending on the size of the curvature, this is typically done in one of three ways: bracing, surgery, or postural positioning through customized cushioning. Stopping the progression of the scoliosis can prevent the loss of function in many activities of daily livingby maintaining range of motion, preventing deformity of the rib cage, and reducing pain during activities such as bending or lifting.

Occupational therapists are often involved in the process of selection and fabrication of customized cushions. These individualized postural supports are used to maintain the current spinal curvature, or they can be adjusted to assist in the correction of the curvature. This type of treatment can help to maintain mobility for a wheelchair user by preventing the deformity of the rib cage and maintaining an active range of motion in the arms.

For other self-care activities (such as dressing, bathing, grooming, personal hygiene, and feeding), several strategies can be used as a part of occupational therapy treatment. Environmental adaptations for bathing could include a bath bench, grab bars installed in the shower area, or a handheld shower nozzle. For activities such as dressing and grooming, various assistive devices and strategies can be used to promote independence. An occupational therapist may recommend a long-handled reacher that can be used to assist self-dressing by allowing a person to avoid painful movements such as bending over; a long-handled shoehorn can be used for putting on and removing shoes. Problems with activities such as cutting meat and eating can be addressed by using specialized cutlery, kitchen utensils, or dishes.

Bracing is normally done when the patient has bone growth remaining and is, in general, implemented to hold the curve and prevent it from progressing to the point where surgery is recommended. In some cases with juveniles, bracing has reduced curves significantly, going from a 40 degrees (of the curve, mentioned in length above.) out of the brace to 18 degrees in it. Braces are sometimes prescribed for adults to relieve pain related to scoliosis. Bracing involves fitting the patient with a device that covers the torso; in some cases, it extends to the neck. The most commonly used brace is a TLSO, such as a Boston brace, a corset-like appliance that fits from armpits to hips and is custom-made from fiberglass or plastic. It is sometimes worn 22–23 hours a day, depending on the doctor's prescription, and applies pressure on the curves in the spine. The effectiveness of the brace depends not only on brace design and orthotist skill but on patient compliance and amount of wear per day. The typical use of braces is for idiopathic curves that are not grave enough to warrant surgery, but they may also be used to prevent the progression of more severe curves in young children, to buy the child time to grow before performing surgery, which would prevent further growth in the part of the spine affected.

Indications for Scoliosis Bracing: Scoliosis professionals determine the proper bracing method for a patient after a complete clinical evaluation. The patient’s growth potential, age, maturity, and scoliosis (Cobb angle, rotation, and sagittal profile) are also considered. Immature patients who present with Cobb angles less than 20 degrees should be closely monitored. Immature patients who present with Cobb angles of 20 degrees to 29 degrees should be braced according to the risk of progression by considering age, Cobb angle increase over a six-month period, Risser sign, and clinical presentation. Immature patients who present with Cobb angles greater than 30 degrees should be braced. However, these are guidelines and not every patient will fit into this table. For example, an immature patient with a 17-degree Cobb angle and significant thoracic rotation or flatback could be considered for nighttime bracing. On the opposite end of the growth spectrum, a 29-degree Cobb angle and a Risser sign three or four might not need to be braced because there is reduced potential for progression.

Surgery is indicated by the Society on Scoliosis Orthopaedic and Rehabilitation Treatment (SOSORT) at 45 degrees to 50 degrees and by the Scoliosis Research Society (SRS) at a Cobb angle of 45 degrees. SOSORT uses the 45-degree to 50-degree threshold as a result of the well-documented, plus or minus five degrees measurement error that can occur while measuring Cobb angles.

Scoliosis braces are usually comfortable for the patient, especially when it is well designed and fit; also after the 7 to 10-day break in period. A well fit and functioning scoliosis brace provides comfort when it is supporting the deformity and redirecting the body into a more corrected and normal physiological position.

The Scoliosis Research Society's recommendations for bracing include curves progressing to larger than 25°, curves presenting between 30 and 45°, Risser sign 0, 1, or 2 (an X-ray measurement of a pelvic growth area), and less than six months from the onset of menses in girls.

Progressive scolioses exceeding 25° Cobb angle in the pubertal growth spurt should be treated with a pattern-specific brace like the Chêneau brace and its derivatives, with an average brace-wearing time of 16 hours/day (23 hours/day assures the best possible result).

The latest standard of brace construction is with CAD/CAM technology. With the help of this technology, it has been possible to standardize the pattern-specific brace treatment. Severe mistakes in brace construction are largely ruled out with the help of these systems. This technology also eliminates the need to make a plaster cast for brace construction. The measurements can be taken in any place and are simple (and not comparable to plastering). In Germany, available CAD/CAM braces are known such as the Regnier-Chêneau brace, the Rigo-System-Chêneau-brace (RSC brace), and the Gensingen brace. Many patients prefer the "Chêneau light" brace: It has the best in-brace corrections reported in international literature and is easier to wear than other braces in use today. However, this brace is not available for all curve patterns.

Prior to 2013 the efficacy of bracing has not been definitively demonstrated in randomised clinical studies, with more limited studies giving inconsistent conclusions. In 2013 the Bracing in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis Trial (BrAIST) published results establishing benefits of bracing in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis. In the randomized cohort, 72% in the group instructed to wear a brace for 18 hours per day against 48% in the observation group sustained curve progression to under 50 degrees, the proxy used for not requiring surgery. Additionally results suggested that the more a patient wore the brace, the better the result.

In progressive infantile and sometimes juvenile scoliosis, a plaster jacket applied early may be used instead of a brace. It has been proven possible to permanently correct cases of infantile idiopathic scoliosis by applying a series of plaster casts (EDF: elongation, derotation, flexion) on a specialized frame under corrective traction, which helps to "mould" the infant's soft bones and work with their growth spurts. This method was pioneered by UK scoliosis specialist Min Mehta. EDF casting is now the only clinically known nonsurgical method of complete correction in progressive infantile scoliosis. Complete correction may be obtained for curves less than 50° if the treatment begins before the second year of life.

Surgery is usually recommended by orthopedists for curves with a high likelihood of progression (i.e., greater than 45 to 50° of magnitude), curves that would be cosmetically unacceptable as an adult, curves in patients with spina bifidaand cerebral palsy that interfere with sitting and care, and curves that affect physiological functions such as breathing.

Surgery for scoliosis is performed by a surgeon specializing in spine surgery. For various reasons, it is usually impossible to completely straighten a scoliotic spine, but in most cases, significant corrections are achieved.

The two main types of surgery are:

One or both of these surgical procedures may be needed. The surgery may be done in one or two stages and, on average, takes four to eight hours.

Spinal fusion is the most widely performed surgery for scoliosis. In this procedure, bone [either harvested from elsewhere in the body (autograft) or from a donor (allograft)] is grafted to the vertebrae so when they heal, they form one solid bone mass and the vertebral column becomes rigid. This prevents worsening of the curve, at the expense of some spinal movement. This can be performed from the anterior (front) aspect of the spine by entering the thoracic orabdominal cavities, or more commonly, performed from the back (posterior). A combination may be used in more severe cases, though the modern pedicle screw system has largely negated the need for this.

In recent years all-screw systems have become the gold-standard technique for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Pedicle screws achieve better fixation of the vertebral column and have better biomechanical properties than previous techniques, so enabling greater correction of the curve in all planes.

A complementary surgical procedure a surgeon may recommend is called thoracoplasty (also called costoplasty). This is a procedure to reduce the rib hump that affects most scoliosis patients with a thoracic curve. A rib hump is evidence of some rotational deformity to the spine. Thoracoplasty may also be performed to obtain bone grafts from the ribs instead of the pelvis, regardless of whether a rib hump is present. Thoracoplasty can be performed as part of a spinal fusion or as a separate surgery, entirely.

Thoracoplasty is the removal (or resection) of typically four to six segments of adjacent ribs that protrude. Each segment is one to two inches long. The surgeon decides which ribs to resect based on either their prominence or their likelihood to be realigned by correction of the curvature alone. The ribs grow back straight.

Thoracoplasty has risks, such as increased pain in the rib area during recovery or reduced pulmonary function (10–15% is typical) following surgery. This impairment can last anywhere from a few months to two years. Because thoracoplasty may lengthen the duration of surgery, patients may also lose more blood or develop complications from the prolonged anesthesia. A more significant, though far less common, risk is the surgeon might inadvertently puncture the pleura, a protective coating over the lungs. This could cause blood or air to drain into the chest cavity, hemothorax or pneumothorax, respectively.

New implants that aim to delay spinal fusion and to allow more spinal growth in young children have been developed. For the youngest patients, whose thoracic insufficiency compromises their ability to breathe and applies significant cardiac pressure, ribcage implants that push the ribs apart on the concave side of the curve may be especially useful. These Vertical, Expandable Prosthetic Titanium Ribs (VEPTR) provide the benefit of expanding the thoracic cavity and straightening the spine in all three dimensions while allowing it to grow.

An expandable rod, called a growing rod, may be surgically implanted across the segment of spinal curvature, and lengthened, under surgery, every six months to mimic and maintain normal spine growth. This intervention can halt the progress of curvature and gradually straighten the spine.

Although these methods are novel and promising, they are suitable only for growing patients with early-onset scoliosis, and have a high complication rate. Spinal fusion remains the "gold standard" of surgical treatment for scoliosis.

Possible complications may be inflammation of the soft tissue or deep inflammatory processes, breathing impairments, bleeding and nerve injuries. It is not yet clear what to expect from spine surgery in the long term. Taking into account that signs and symptoms of spinal deformity cannot be changed by surgical intervention, surgery remains primarily a cosmetic indication, only especially in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis, the most common form of scoliosis never exceeding 80°. However, the cosmetic effects of surgery are not necessarily stable.

Pain medication

In the event of surgery to correct scoliosis, pain medications and anesthesia will be administered. Before the surgery, the patient will receive anesthesia. With adults, the anesthesia will be administered through an IV in the antecubital region of the arm. With young children, however, the child will be asked to breathe in nitrous oxide, or laughing gas. Because needles can be frightening for a young child, the nitrous oxide will put them to sleep so the anesthesiologist can then insert the IV in order to give them the anesthesia. After the surgery, the patient will most likely be given morphine. Until the patient is ready to take the medicine by mouth, an IV will be giving them their medication. Morphine is the most common pain medicine used after scoliosis surgery, and is often administered through a patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) system. The PCA system allows the patient to push a button when they are feeling pain, and the PCA will emit the drugs into the IV and then into the body. To prevent overdoses, there is a limit on the number of times a patient can push the button. If a patient pushes the button too much at once, the PCA will reject the request.

Bowel and bladder function

For the patient's bladder control, a catheter will be inserted so that a patient can urinate without having to move. A catheter is inserted because the patient will not have much free movement to be able to get up and walk to the bathroom. The most common type of catheter used after major surgeries is an indwelling Foley catheter. The indwelling Foley catheter is most often put in the urethra, with a tube leading into a drainage bag. Once the catheter is inserted into the urethra, a balloon is blown up inside the bladder in order to keep it from falling out. The balloon allows the catheter to remain inside the urethra until the patient is able to get up and go to the bathroom on their own. The drainage bag is connected to the side of the bed, and must be changed or emptied out once it is full.

Bowel control can vary from patient to patient. The combination of no food, very little fluids, and a lot of prescription drugs has the potential to cause many patients to become constipated. The body is used to a normal diet, and used to excreting waste in a system. Interrupting the system can cause bowel problems. This constipation can be resolved in a couple of ways. The first way, and the most common way, is to administer a rectal suppository. A rectal suppository is administered through the anus, and into the rectum. They are bullet-shaped and contain medicine that will help the patient's bowels get back on track. Once the suppository is inserted, it is designed to melt off the wax-like case, and put the medicine in the body. If the suppository does not work, a laxative may be continued at home to keep the bowels in full function.

Diet

When first returning home after surgery, a nutritional diet is necessary in order to keep the body operating correctly. Junk food is not a good idea, as the grease and sugar can irregulate the bowels. Fruit, vegetables, and juices will be a vital part in the diet.Food and drink will be limited for the patient after surgery. Because the bowels are not fully active because of anesthetic, clear water and ice may be the only acceptable thing to ingest. After the digestive tract is back up to speed, soft food and drink like pudding, soup broth, and orange juice are acceptable. Very dark urine with a strong odor means that the person is most likely dehydrated and needs more fluids. In order for the urine to become a pale or clear color, the patient will need to drink a lot of water. Juices such as prune juice are a healthy option and prune juice also helps with constipation, a common factor after surgery. When it comes to food, whole grains should be added into the diet. Whole grains can be broken down easily by the body whereas processed grains and flour cannot be broken down easily. Processed grains and flour also add to constipation.

Generally, the prognosis of scoliosis depends on the likelihood of progression. The general rules of progression are larger curves carry a higher risk of progression than smaller curves, and thoracic and double primary curves carry a higher risk of progression than single lumbar or thoracolumbar curves. In addition, patients not having yet reached skeletal maturity have a higher likelihood of progression (i.e., if the patient has not yet completed the adolescent growth spurt).

Scoliosis affects 2–3% of the United States population, which is equivalent to about 5 to 9 million cases. A scoliosis spinal column's curve of 10° or less affects 1.5% to 3% of individuals. The age of onset is usually between 10 years and 15 years (can occur at a younger age) children and adolescents, making up to 85% of those diagnosed. This is seen to be due to rapid growth spurts occurring at puberty when spinal development is most relenting to genetic and environmental influences. Because female adolescents undergo growth spurts before postural musculoskeletal maturity, scoliosis is more prevalent among females. Although fewer cases are present today using Cobb angleanalysis for diagnosis, scoliosis remains a prevailing condition, appearing in otherwise healthy children. Incidence of idiopathic scoliosis (IS) stops after puberty when skeletal maturity is reached, however, further curvature may proceed during late adulthood due to vertebral osteoporosis and weakened musculature.

|

Page Content |